The need for a new migration paradigm

Migration is one of the most hotly debated, but also one of the least understood public issues. The main problem is not so much a lack of knowledge, but rather the polarized nature of the migration debate; particularly its framing in simplistic, dichotomous pro- and anti-terms. Indeed, debates have become so polarized that most nuance gets lost, with pro- and anti- migration camps often exaggerating the harms and benefits of migration by cherry picking only the facts that fit their narrative.

Meanwhile, all the rhetoric and polarization around migration distract the attention away from the real questions: Why have over three decades of border controls failed to stop the suffering at our borders? Why have governments failed to address the exploitation of migrant workers? And why have politicians, despite all their tough talk, consistently been failing to deliver on their promises?

In fact, if we look at actual long-term outcome of policies, they often turn out to be the polar opposite of what was promised to us.

For instance, why did net immigration to the UK nearly quadruple in the wake of Brexit – the whole purpose of which was to ‘take back control’ over immigration? Why has the EU failed to effectively manage migration ever since the early 1990? Why have nearly four decades of massive investments in border enforcement on the US-Mexico border resulted in 11 million undocumented migrants living and working in the country?

Why is the actual effectiveness of policies rarely the subject of serious debate? Why has the migration debate been stuck for so many years?

The truth is that most current migration debates are not genuine debates at all, in their almost exclusive focus on opinion or wishful thinking rather than fact – on what migration ought to be, rather than on what migration is in terms of its actual trends, patterns, causes and impacts, and how policies could best deal with the realities on the ground to produce desired outcomes and avoid the errors of the past.

As I argue in my book How Migration Really Works, immigration policies often fail to deliver – or have actually backfired – because they are not based on a genuine understanding of migration processes. On the one hand, this is because the truth about migration gets systematically distorted by politicians, NGOs and international organizations which have particularly biased views of migration. On the other hand, most debates – and policies – about migration are based on simplistic, deeply flawed assumptions about the very nature and causes of migration.

Conventional ideas about migration are closely associated to the so-called ‘push-pull’ model, which has achieved near-total hegemony in popular thinking, education as well as migration narratives peddled by media, pundits and politicians. Push–pull models usually identify economic, environmental and demographic factors which are assumed to ‘push’ people out of countries of origin and ‘pull’ them into destination countries.

Particularly within the context of so-called ‘South-North migration’

push-pull models typically portray the ‘root causes’ of migration as an outflow of factors like poverty, unemployment, violence, population growth and environmental degradation linked to climate change, supposedly leading to increasingly massive displacement.

The mirror image is that the safety and welfare provisions of Western states would be important ‘pull factors’, leading to fears that this will ‘suck in’ unsustainably high numbers of migrants and refugees. Hence, the seemingly logical policy implication that rich countries should severely restrict the immigration of lower-skilled migrants and refugee, in order to preserve welfare provisions, health care, education and affordable housing for native populations.

Based on this analysis, the only durable long-term solution would be to address the ‘root causes’ of migration by reducing poverty, unemployment and violence in origin countries. This idea is frequently echoed by political leaders, both in the so-called ‘Global North’ and the ‘Global South’: the only way to tackle the border crisis is to address the ‘root causes’ of migration by stimulating development in origin countries.

For instance, this ‘root causes’ approach was one of the central premises of the migration policy of the Biden administration as well as of various ambitious schemes suggested by EU (and African) politicians for a ‘Marshall plan for Africa’, by using development aid to help poor people to stay at home. This assumption is deeply rooted in ‘push-pull’ thinking: if push factors are reduced, fewer people are expected to leave their countries.

Push-Pull: A migration quasi-science

The familiar push-pull framework continues to hold appeal, because of its apparent ability to incorporate all major factors affecting migration decision-making. Yet, despite its appeal and widespread use, the push-pull model is unable to explain a whole range of empirical paradoxes, which reveals its quasi-scientific nature.

For instance, if poverty and destitution are the root cause of migration, why do the world’s poorest countries tend to have the lowest long-distance emigration levels? Why does emigration typically increase when low-income countries ‘develop’, become richer and income gaps with destination countries actually decrease?

If ‘population pressure’ really drives migration, why do most migrants move from relatively sparsely populated areas to densely populated areas? Why is emigration generally highest from middle-income countries where population growth is declining fast? If environmental degradation really pushes people off the land, why does long-distance migration often decrease during droughts and floods?

And - perhaps most importantly - why do most people not migrate despite the abundance of alleged ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors? Depending on estimation methods, over the past six decades international migrants have represented roughly 3-3.6% of the world’s population. This share has remained rather stable, challenging the notion that world migration is spiralling out of control. This means that at least 96 percent of the world’s population is living in their native country, despite the prevalence of problems like poverty, inequality and violence, and despite revolutionary improvements in transport and communication technology.

Kerilyn Schewel, a migration researcher based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has therefore argued that common views on migration suffer from a mobility bias: by focusing on the causes of migration and the small minority of humankind who actually cross international borders we tend neglect the countervailing structural and personal forces and motives that that compel the overwhelming majority of people to stay at home.

Migration as an intrinsic part of development

We therefore need an entirely new way of thinking about migration, a new paradigm of migration that belies almost everything that is usually said and we tend to believe about human mobility. This is particularly true for conventional analyses of so-called ‘South-North’ migration, which often reflects worn stereotypes about the ‘Third World’ (as pools of all sorts of human misery) and and misguided assumptions rather than empirical evidence.

We urgently need a new vision on migration, based on facts rather than fears, based on evidence rather than ideology. By necessity, such an alternative, scientific paradigm on migration should be a holistic perspective, one that analyses migration as an intrinsic part of broader development processes, instead of somehow the antithesis of development and a ‘problem to be solved’ (or, alternatively, a ‘solution to problems’, which equally reflects a biased, rather ideological take on migration).

This requires a radical departure from standard analysis of ‘South-North’ migration. Indeed, rather than a stereotypical ‘desperate flight from misery’, numerous studies have shown that migration is generally an investment in the long-term well-being of entire families, and something that requires significant resources.

In an article published in 2021, A Theory of Migration: The Aspirations-Capabilities Framework, I therefore argued that we need to reconceptualize human mobility as a function of people’s aspirations and capabilities to migrate within given sets of perceived opportunity structures. Migration, particularly over long distances, requires significant economic resources, social connections and ‘cultural capital’ such as in the form of knowledge, skills and diplomas.

From this perspective, we need to consider migration as an investment and resource rather than a stereotypical ‘desperate flight from misery’. However, it is also a reaction to profound, largely irreversible changes in people’s subjective ideas about the ‘good life’, which typically occur as societies go through fundamental cultural changes linked to education, modernization and media access.

The resulting capabilities-aspirations framework helps us understand the complex – and often counter-intuitive – ways in which broader processes of social transformation shape trends and patterns of migration. For instance, it helps us to explain why development and the profound social transformations usually accompanying modernization processes in low-income countries generally increases migration, as factors like poverty reduction, increasing education and better infrastructure tend to simultaneously increase people’s capabilities and aspirations to move within and across borders.

The illusionary quest to halt the ‘rural exodus’

Similarly, we need to see rural-to-urban migration as an intrinsic, and therefore largely inevitable, part of urbanization processes. Urbanization in turn is part of a broader transformation from rural- agrarian to urban-industrial economies as well as fundamental, largely irreversible cultural changes in aspired lifestyles that increase people’s desire to live in urban environments.

This helps to explain why repeated attempts by governments of developing countries to stem the so-called ‘rural exodus’ have invariably failed. In fact, they were bound to fail, as they failed to acknowledge that industrialization and economic development are contingent on people moving from rural places to towns and cities.

For instance, the extraordinarily fast economic growth of China was conditional on, and predicated by, the large-scale transfer of workers (and their families) from rural to urban areas. In 1980, about 19 percent of the Chinese were living in urban areas. In 2023, this has shut up to 65 percent. This extraordinary growth is partly explained by population growth in urban areas, but internal migration has been a big part of it.

It is therefore as impossible to understand the modern experience of rural-to-urban migration without understanding urbanization, as it impossible to understand urbanization without understanding the central role of migration in the process.

The inseparable, interdependent relation between migration and urbanization is perhaps the best example to illustrate the need to reconceptualise migration as an intrinsic part of broader processes of social transformation and development instead (naively) of a ‘problem to be solved’.

For the same reason, it is very difficult to stop international migration unless we would be willing, and be able, to reverse the underlying fundamental trends of capitalist development, industrialization and modernization. And this is not only about economics and the quest for better jobs and higher income. It has an important cultural dimension too.

‘Developmental’ factors such as increasing education and media access typically changes young people’s aspirations levels and ideas of the ‘good life’, in such ways that this often makes them desire to relocate, from villages to towns to cities, or abroad. This reveals the need to adopt a broader social transformation perspective in analysing migration that includes cultural and social change instead of more limited, income-based definitions of development.

Why emigration rises as poor countries get richer

This new paradigm of migration as development also yields a very different understanding of how development processes shape international migration in quite surprising, counter-intuitive ways that defy simplistic push-pull models. In fact, we have solid evidence that emigration levels generally tend to rise as poor countries get richer.

These insights are anything but new. Since the 1970s, geographers and demographers, and most notably Wilbur Zelinsky and Ronald Skeldon, have argued that development and modernization initially tend to boost internal and international mobility. These insights resonated with Timothy Hatton and Jeffrey Williamson’s monumental study of the large-scale migration of some 55 million Europeans to the Americas and Australia between 1850 and 1914. However, a lack of comprehensive data prevented this theory to be validated for recent global migration trends.

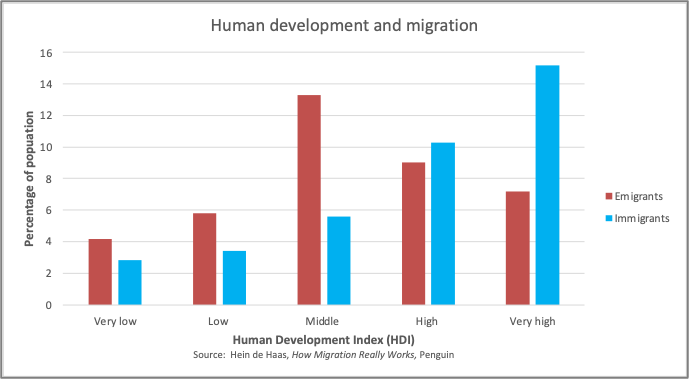

In 2010, the release of unique, new global estimates on migrant populations enabled me to test whether these patterns hold for contemporary migrations, by studying the relationship between levels of development and trends in immigration and emigration. Graph 2 depicts the relation between levels of human development (a composite index based on education, income and life expectancy indicators) and levels of immigration and emigration measured as the immigrant and emigrant shares of the total population of countries.

The basic pattern, which has been largely confirmed by several follow-up longitudinal statistical studies, particularly by the prominent migration economist Michael Clemens, is depicted in Graph 2. On the one hand, the graph reveals a linear and positive association between levels of development and levels of immigration that is rather intuitive. As we might expect, the wealthier and more ‘developed’ countries are, the more migrants they tend to attract. In the wealthiest countries of the world, immigrants represent on average about 15 per cent of the population.

This corroborates the idea that rising levels of immigration are the almost-inevitable by-product of long-term growth and prosperity, particularly when such growth creates labour shortages that typically attract migrant workers. As we will see, another important lesson to bearing in mind our new paradigm of migration as development.

However, the real surprise is in the non-linear relation between levels of human development and levels of emigration. The graph indicates that emigration tends to go up when poor countries become richer and only tends to go down when countries move from middle- to high-income status. Emigration typically peaks at mid-development levels, at which an average of about 13 per cent of the population is living abroad.

So, emigration initially rises as poor countries get richer and only decreases when they shift from the middle-income into the higher-income category. Estimates by Michael Clemens from (2020) suggested that, on average, emigration levels would start to decline when countries cross a tipping point of per capita GDP income levels of about $10,000 (corrected for purchasing power parity), ‘peak emigration’ levels of development that high-emigration countries like Morocco, the Philippines and Guatemala would be nearing.

The migration transition

So, the relation between ‘development’ and levels of out-migration is thus fundamentally non-linear. The idea that development leads to more migration defies the push-pull model and the standard migration narrative we hear in the media.

The aspirations-capabilities framework can also help us to understand why migration typically rises as poor countries get richer. As countries transition from low to middle-income societies, international out-migration tends to increase fast because declining poverty and sociocultural change tied education and media access simultaneously increases people’s aspirations and capabilities to migrate. Beyond some point of development, usually somewhere between middle- and high-income status, emigration levels will generally start to decrease, as more and more people will be able to realize their life aspirations in their own countries.

As a consequence of progressed economic development and other changes such as population ageing and the increasing skill-levels of the domestic workforce, labour shortages will start to appear, particularly in lower skilled jobs, which tend to attract immigrants. In this way, countries will gradually transition from being net emigration countries to net immigration countries. Such ‘migration transitions’ happened in a not-too-distance past in countries like Ireland, Italy, Spain, South Korea and Thailand, and now appear to be underway in Mexico, Turkey and several other emerging economies.

Although we should be careful not to blindly apply such schemes to individual countries – as there is a lot of variation behind the averages – this alternative paradigm leads to very different view on how future development might shape migration from low-income countries.

Take Sub-Saharan Africa, for instance. It is the least migratory region in the world, partly because of the high incidence of poverty and poor connectivity. Any form of development is therefore likely to lead to more, instead of less, migration within and from Africa.

Mobility as freedom

All of this suggest that we have to challenge, and in many ways reverse, usual analyses of migration and mobility. At a more fundamental level, this requires an entirely different way of conceptualizing mobility: not reducing people to passive objects or victims that are supposedly ‘pushed’ and ‘pulled’ around that world by macro-forces. And if we seek to understand why some people migrate, we must also ask why most people actually do not move.

We therefore need to redefine human mobility not so much as the act of moving (which is often the rather narrow, frame of analysis), but as people’s capability to choose where to live, including the option to stay. This yields a vision in which moving and staying are seen as complementary manifestations of migratory agency. From this perspective, human mobility constitutes a fundamental, intrinsically wellbeing-enhancing freedoms, akin to the freedom of thought, expression and religion as well as political and economic rights.

In this light, refugees are not forced migrants because they lack agency or resources (many posses both, otherwise most of them could not have fled) but because they had no reasonable option to remain. Obviously, the root cause of refugee migration is violent conflict and oppression. Yet not all people will flee in such circumstances. Some may want to flee but may lack the resources to do so. Others may prefer to remain, to protect loved ones and belongings. And most people who do flee prefer to stay close to home, often settling in adjacent areas of neighbouring countries.

This philosophical perspective of ‘mobility as freedom’ also helps us to move beyond narrow, economistic, pecuniary understandings of migration as a means-to-and-end. People can get profoundly upset when their fundamental mobility rights are taken away. The public outrage erupting during the Covid lockdowns, starkly revealed the extent to which most (Western) people take their mobility freedoms for granted; and the extent to which people become angry, frustrated and depressed if these are restricted.

For largely similar reasons, the inability to migrate can trigger powerful feeling of frustration and deprivation, whether from opportunities to better life chances, to try our life, to explore new horizons, or, to flee violence or persecution. Yet, due to poverty and migration restrictions, many people aspire to migrate but actually lack the capabilities to do so. In this context, the Norwegian migration researcher Jørgen Carling has argued that we may not be living in an age of migration, but rather in an age of ‘involuntary immobility’.

The myth of climate migration

We must then understand mobility as a fundamental freedom, as an investment in a better future, and as a source rather than as an act of desperation. Once again, these insights reveal the necessity of fundamentally challenging, and in many ways reversing, usual schemes of analysis based on misguided ‘push-pull’ models. Ironically, the very factors that are assumed to be ‘push’ factors (such as poverty and deprivation) are often factors that actually prevent people from migrating. Impoverishment and deprivation can actually lead to less migration, as it tends to deprive people of the means to do so.

As I argue in How Migration Really Works, these insights also cast doubt on the conventional idea that climate change will trigger massive international migration. While environmental degradation may actually deprive people of the means to move, migration, particularly over long-distances is expensive, and frequently inaccessible to the poorest. While environmental degradation may heightens people’s migration aspirations, it can simultaneously effectively decrease their migration capabilities, rendering the net effect theoretically ambiguous. Empirical studies reinforce this point: research conducted in Mali, Malawi and Burkina Faso has shown that droughts decreased long-distance migration from rural areas to cities and foreign destinations.

For this reason, there is an increasing scientific consensus that environmental degradation – whether or not caused by climate change – is unlikely to lead large-scale international displacement, as prophecies by pundits and frequent headlines about massive climate migration make us believe. In reality, the biggest victims of environmental (or economic or political) havoc are often those who lack the capabilities to migrate and are therefore trapped in potentially dangerous situations of ‘involuntary immobility’. Any genuine concern about the adverse effects of climate change should therefore focus on those unable to move at all.

The real root causes of migration

One of the most important insights offered by the new paradigm of migration as development is this: neither poverty nor inequality, but rather labour demand is the most important driver or ‘root cause’ of immigration. Thriving economies tend to generate increasing labour shortages, particularly in lower-skilled, manual and unattractive jobs, for which domestic labour supplies run dry as the native population gets better educated and prefer to do more attractive jobs they deem below their status. Declining birth rates and population ageing consistently exacerbate such labour shortages.

The political rhetoric that immigrants are coming to live off welfare, take jobs from locals or getting involved in crime, obscure a fundamental truth: most migrants come to fill labour shortages. This is not so much because ‘Third World people’ would be magically drawn to the honeypots of Western welfare systems, but rather because migrants fill in critical labour shortages.

While in low-income countries tends to increase their emigration potential, most migrants wouldn’t invest significant amounts of money, or take the risks of crossing borders illegally, unless they didn’t have a reasonable prospect that these investments would eventually pay off. And this is not about living on welfare or crowding out local workers, but mostly about doing essential work in sectors such as agriculture, food processing, hospitality, construction, delivery, cleaning, home maintenance and domestic work.

Growing labour shortage in higher and, particularly, lower-skilled, manual occupations have been the main reason why immigration levels in Western countries have consistently gone up over the past decades. This further corroborates with earlier evididence (see graph x) already reinforced: immigration is the almost-inevitable by-product of growth and prosperity.

In other words: Migrants don’t take jobs, but are filling vacancies. For instance, one major driver why both legal and illegal immigration to the US, the UK (despite ‘Brexit’!) and the EU peaked in the 2022 and 2023 were the exceptionally high labour shortages in the post-Covid years. As economies – particularly in the US – made a very strong come-back, many workers who lost their jobs during the pandemic didn’t return to their jobs. This post-Covid ‘labour crunch’ was a major factor behind the unprecedented labour shortages and, hence, the surge in immigration.

While the arrival of refugees – such as from Ukraine to the EU, and from Central America and Venezuela to the US – played a role too, refugees constitute a smaller share of total migration than political rhetoric and media images suggest. In the longer term-refugees form about 10 percent of overall global migration levels. Apart from international students, the rest is mainly about workers and family members joining these labour migrants sooner or later.

The most effective way to bring down immigration

This reality of migration starkly contradicts political narratives claiming that ‘we don’t need migrant workers’. The demand for lower-skilled migrant labour is real and consistent. Consequently, migrant workers are not as ‘unwanted’ as politicians often claim: employers and agencies actively recruit foreign workers, as migrants fill crucial job shortages in vital sectors.

Immigration restrictions that deny the central role of destination country labour demand in driving migration will therefore not stop immigration. Instead, they rather prompt migrant workers to overstay their visas or cross borders illegally. Another unintended effect of ill-conceived immigration restrictions is that they prompt temporary migrant workers to cancel return plans, and subsequently push them into permanent settlement, thereby triggering significant ‘chain migration’ in the form of family members joining then.

In the US, for instance, research by the sociologist Douglas Massey and his colleagues has shown that massive investments in border enforcement since the late 1980s – pursued by both Republican and Democratic administrations – turned a largely seasonal and circular flow of Mexican workers going back and forth mainly to California and Texas into an 11-million-strong population of permanently settled families living all across the United States.

Politicians find it hard to admit the fundamental truth that immigration is largely driven by labour demand. This would go against their main talking point that only higher-skilled migrants are needed and that lower-skilled workers have no jobs to come to. That’s a lie, and they know it. The truth is that our wealthy, ageing and highly educated societies have developed a built-in structural dependency on migrant workers that is impossible to eliminate as long as our economies keep growing. (Aand even more so if politicians want to maintain ‘flexible’ labor markets with minimum ‘Big Brother’ state intrusion).

This is visible in the correlation between business cycles and (legal and illegal) immigration. The logic is simple. If the economy is doing well and unemployment is low, employers will find it more difficult to find workers, which makes them more likely to hire migrants. If the economy tanks, and unemployment is rising, few migrants will see the point in coming, and, particularly if migration is free, many will return, at least temporarily.

Viewed from this perspective, the most effective way to bring down immigration is to wreck the economy.

An organized political hypocrisy

Yet, this is of course precisely what nobody wants: You cannot have a thriving and open economy, and much lower migration. When it comes to immigration, governments cannot have their cake and eat it too.

Many politicians, however, are afraid to admit this fundamental truth, not only out of fear of being seen as ‘soft on immigration’, but also because it would contradict their own talking points and propaganda about migrants being a threat to prosperity, welfare and security.

This creates a powerful incentive for politicians to create a semblance of being in control through bold acts of political showmanship (through tough rhetoric, deportations and border crackdowns) that conceal the true nature of immigration policies, which are much more liberal than all the tough rhetoric seems to suggest.

An analysis of 6500 policy measures I carried out with my former team at Oxford University revealed that, over the past decades, immigration policies have become more liberal, not more restricted. In other words, despite political rhetoric suggesting the contrary, we opened more doors for legal immigration. We also found that right-wing parties are not much more restrictive than those on the left when we look at the actual policies that are implemented on the ground.

This exposes the huge ‘discursive gap’ between the tough rhetorics and the actual policies on the ground. Not in the least, this is because politicians are under huge pressure from corporate lobbying to create more legal channels for higher and lower-skilled workers for which shortages exist and to turn a blind eye towards the employment of undocumented migrants in essential jobs in key sectors such as agriculture, hospitality, construction and domestic work. Time and again, corporate lobbies play a key role in ‘softening’ tough policies. For instance, lobbies from farmers and the hospitality sector played a big role in Donald Trump’s rather predictable decision in June 2025 to pause most raids targeting farms and hospitality workers after intensive lobbying by employers.

The (huge) elephant in the room of the migration debate

This is the big elephant in the room of the migration debate: the very migrants politicians insist their arrival should be prevented or should be deported, are in fact workers performing essential labour in a wide range of sectors. From agriculture to catering, from cleaning to delivery, and from care work to construction. Most of these migrants are legal, others are undocumented. Yet, in practice, politicians are more than willing to turn a blind eye towards the systemic exploitation of these workers.

The clearest evidence of this hypocrisy is the laughably low level of workplace enforcement, where inspections and routine checks of immigration status and other papers would serve as the most direct deterrent. Indifference to workplace enforcement perpetuates the suffering and insecurity of migrants and refugees. It also leaves largely unpunished the widespread exploitation of undocumented migrant workers, who are regularly minors.

In the United States, for instance, Justice Department records reveals that, prosecutions of employers nationwide rarely exceed15-20 cases annually. Fines for infractions have been symbolic at best, currently ranging from $676 to $5,404 per worker for an employer’s first offence, and these fines are routinely negotiated down These amounts are so low that employers view the tiny chance of being charged as a normal risk and a cost of doing business. When raids take place, it’s usually undocumented workers who suffer consequences such as through detention or deportation, not the employers. Things is little different in the UK and across much of Europe.

All of this reveals the organized political hypocrisy on migration, driven by the fear and unwillingness of politicians on the left and right to tell the truth about migration. The public debate has become more and more decoupled from the realities of immigration policymaking. For decades now, politicians have been duping the public about the true nature of their immigration policies. This is disingenuous. It also highlights the hole politicians dug for themselves as they got caught up in their own migration lies.

The debate we need

Yes, we have a migration crisis. The inability to effectively address illegal migration, the exploitation of (documented and undocumented) migrant workers and concerns about integration and segregation are real problems that would be foolish to deny. However, this is not so much a crisis of numbers, but a political crisis, rooted in the inability or rather unwillingness to acknowledge the true nature and causes of migration, to have a real debate about migration and develop policies that actually work. This is why it is so important to adopt a new, more realistic paradigm for understanding migration, to replace the propaganda misguided assumptions that have misinformed debate and policy for too long now.

Therefore, we urgently need a holistic vision of migration – not as a problem to be solved, or as a solution to problems, but as an intrinsic part of broader processes of social, cultural and economic change that affect our societies. We need to go beyond the usual, simplistic and debilitating framing of migration debates in simplistic and polarizing pro- and anti-terms, and to not focus on what migration ought to be, but rather on what migration is, in terms of its actual trends, patterns, causes and impacts.

Understanding the inevitability of migration, and its central role in economic development and social transformation, will lead us to a totally new way of understanding human mobility – a new paradigm on the very nature and causes of migration that belies almost everything that we are usually told on the subject.

The power of a scientific, and above all nuanced view of migration as part of broader development helps us to understand and – to a certain extent – predict how migration will evolve as our societies and economies change. Adopting this new paradigm bears some important lessons for policy and public debate but, most importantly, it challenges the popular representation of migration as something than can be turned on and off like a tap.

In reality, migration is a partly autonomous process that driven by powerful social, cultural and economic trends in origin and destination countries that largely lie beyond the reach of migration policies. This is the main reason why ill-conceived border policies that ignore the real drivers or ‘root cause’ of migration (notably destination country labour demand but also other factors such as conflict in the case of refugee migration) tend to be ineffective or even become counterproductive.

All of this does not imply that governments cannot or should not control migration. Rather, it highlights the importance of looking beyond migration policies per se. Policies that seem to have nothing to do with migration, can have deep consequences for migration patterns. This points to the importance of aligning migration policies with non-migration policies in the areas of labour markets, education, health care, welfare, and social protection.

For instance, if governments are really serious about wanting more control over – or lower levels of – immigration, this inevitably means drastic economic reform and re-regulate labour markets have to be pursued, which will require a fundamental change in economic policy, and perhaps also lower economic growth in general.

Pursuing this kind of reform will necessitate a radical rethinking of some of the core (‘neoliberal’) principles that have underpinned economic and labour market policy over the last half-century. The irony here is that many politicians who rose to power on an anti-immigration are also in favour of economic deregulation and the dismantling of labour protection, factors that may well increase the demand for migrant workers.

This all point to a deeper truth: we cannot decouple immigration debates from debates about economic policy, labour standards, inequality, welfare, education, and how we treat the sick and elderly. Any real debate on migration will therefore inevitably be a debate on the type of society we want to live in.

The need for a paradigm shift

As I have tried to argue here as well as in my book How Migration Really Works, the frequent failure of migration policies is explained by an inability or unwillingness to understand the complex and often counterintuitive ways in which social, economic, and political transformations affect migration in indirect, but powerful ways, that largely lie beyond the reach of migration policies.

This underscores the urgency of adopting a holistic view that tries to understand migration as an intrinsic and therefore inseparable part of broader processes of social, cultural and economic change affecting societies around the world, and one that benefits some people more than others, can have downsides for some, but cannot be thought or wished away.

If anything, the evidence shows that global migration has very little to do with stereotypical views according to which global migration is essentially about mass movements from the ‘Global South’ to the ‘Global North’ driven by poverty, violence and destitution. In fact, this exposes the whole South-North polarity as highly problematic. As most people prefer to stay, most mobility is within countries, most international migrants move to neighbouring countries, and many low- and, particularly, middle-income countries are important destination countries in their own right.

This reality compels us to reconceptualize migration as a constituent part of development and social transformation, in both origin and destination countries. The implications of adopting this perspective are revolutionary: understanding the inevitability of migration, and its central role in economic development and social transformation, will lead us to a totally new way of understanding human mobility.

Achieving such a fundamental rethinking is imperative to liberate ourselves from the old ways of thinking. The push-pull model is fundamentally flawed in its key prediction and core assumptions about the very nature and causes of migration processes. Therefore, we need nothing less than a paradigm shift if we are to overcome the current polarization and to facilitate more nuanced debates – and more effective policies – about migration.